|

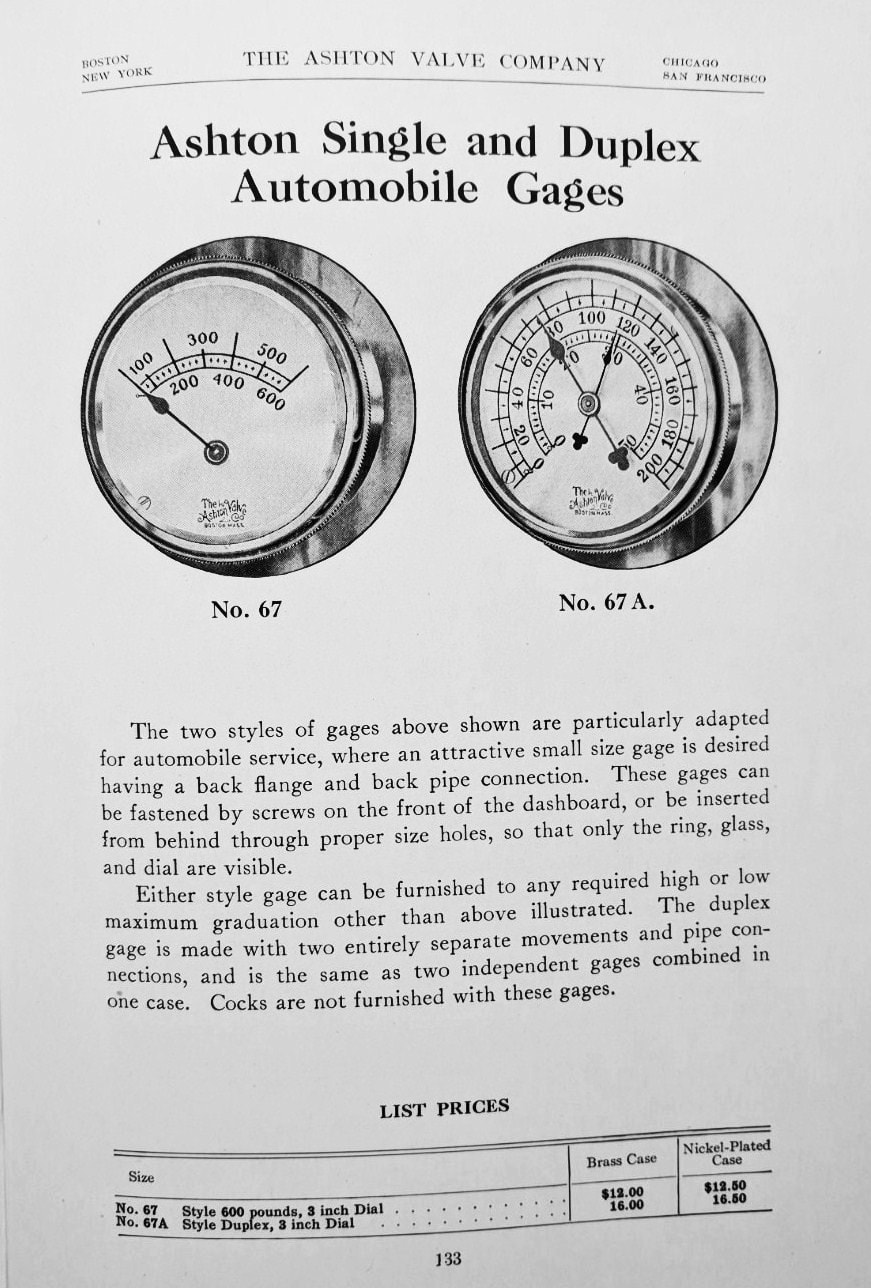

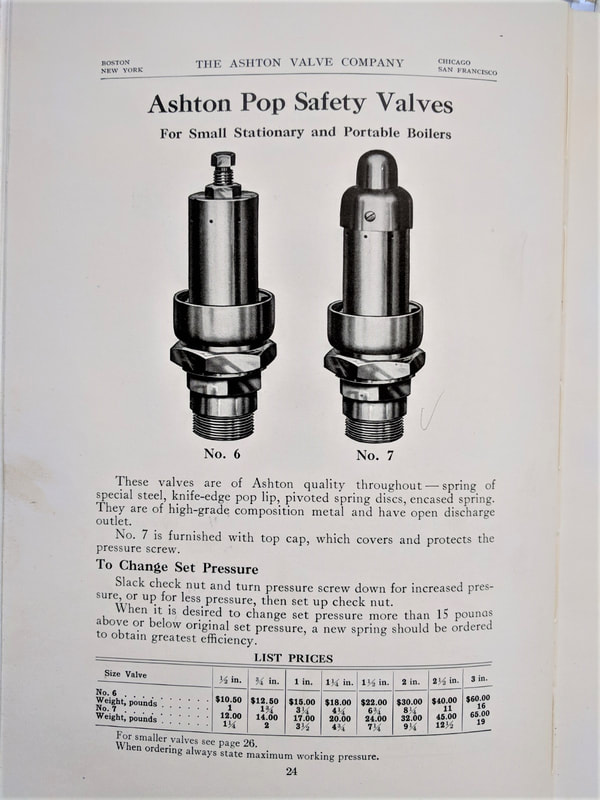

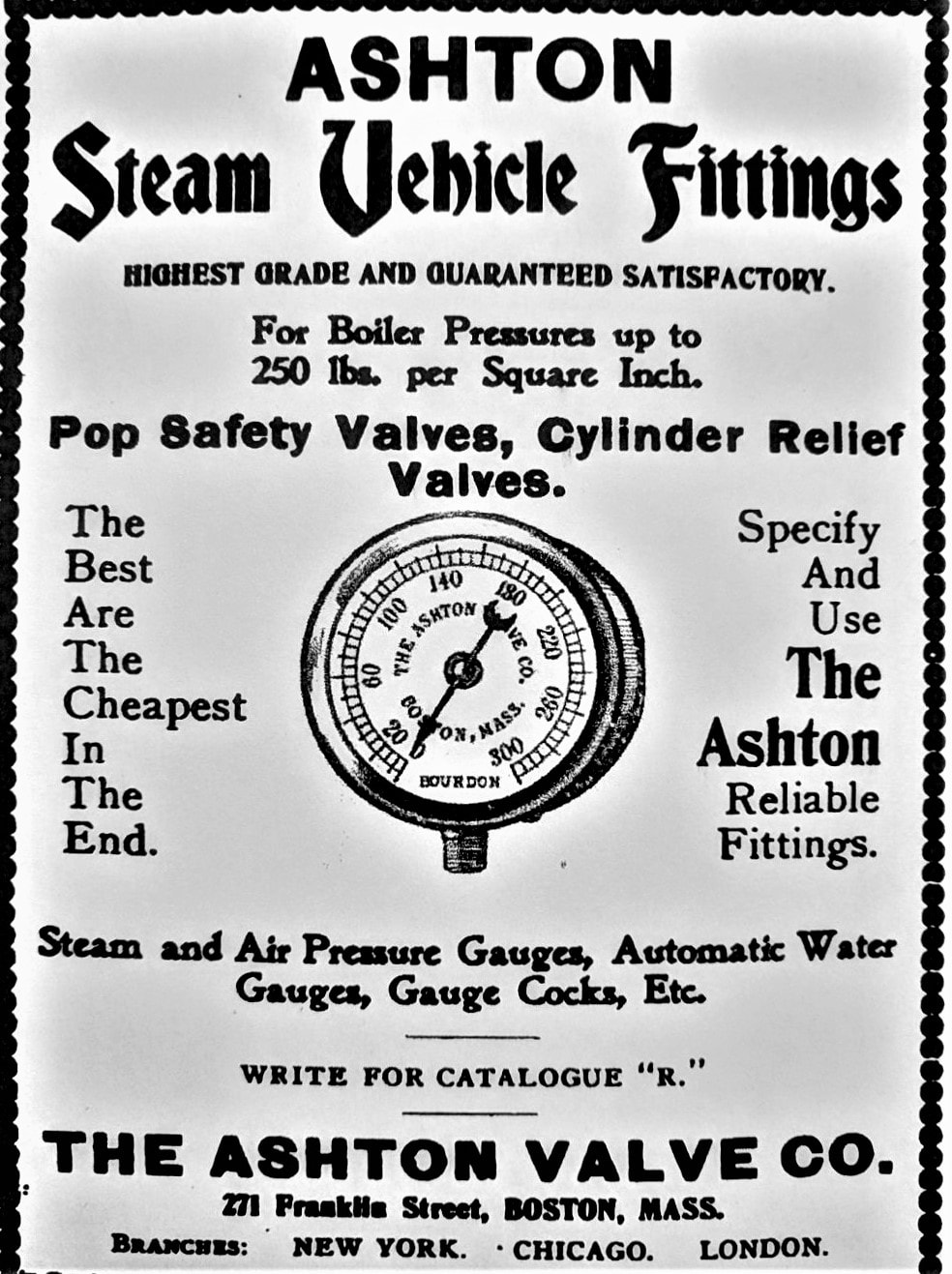

I was sitting with my mom and dad talking about my mom’s side of the family and what I had recently learned about them. My Dad said, “Why don’t you try and find some information on the Ashton side of the family?”. “Sure”, I replied. I immediately found Ashton Valve online. Most of the references were links to Ashton items that had sold on Ebay. It wasn’t long before I had photographs of long deceased relatives that my Dad had never seen before. My scrapbooks soon filled with hundreds of old advertisements and articles I had downloaded from turn of the century steam trade journals. The book shelves at my house started to fill with old gauges and other artifacts related to Ashton Valve purchased on Ebay. One of my friends who happens to be a steam enthusiast suggested I visit the annual “Steam Up” at the New England Wireless and Steam Museum in Rhode Island. I contacted the people running the museum and they loved my idea of having an Ashton Valve exhibit at the event. I honestly had my doubts that anyone would care about a largely forgotten company. I was wrong. Quite a few people asked me questions about the company and told their stories about working with steam. I had purchased a CD online of old Ashton Valve catalogs and the man who sold it to me surprised me by showing up at the show and giving me a safety valve from 1874, and a stock certificated dated 1877. That day in Rhode Island was very inspirational to me. Not long after that, the same friend who told me about the “Steam Up” mentioned a museum he had visited some years back that had sponsored a steam show he thought was excellent, and suggested I check out the museum sometime. It was the Charles River Museum of Industry and Innovation. A few emails and a couple of visits later and here I am, talking about Ashton Valve and looking forward to the exhibit that will be here sometime this year. I’ll be talking about a company that lasted over 100 years, a company that started with 4 employees and a vision to try and make boilers safer. At their peak, they employed around 300 people and were known worldwide for their quality products used in locomotives, ships, and power houses. I would also like to think their products saved a few lives along the way, because boilers can be like bombs. Ashton Valves was born out of Henry Ashton’s desire to make boiler rooms a safer place to work. In the mid to late 1800’s people were dying at an alarming rate. In one year in the mid 1860’s more than 1,000 people died due to boiler explosions and even more were injured. In April of 1865 the paddle steamer “Sultana”, carrying Union prisoners back North from Confederate prison camps exploded, resulting in the loss of 1500 lives. Another explosion in July of 1894 at a lumber mill caused the death of 4 workers and did substantial damage to the mill. It was a horizontal tube type boiler and when the explosion occurred the pressure was probably about 500 psi. The boiler head was blown out and the rest of the shell left the boiler room and flew through the air for a distance of over 1200 feet. During it’s flight it passed through the mill and over several houses at a height of about 80 feet. The last 350 feet of it’s flight was through a dense and heavy woods where it cut off everything in it’s path including a tree which was 28 inches in diameter. The insurance company stated “the safety valve did not work.” It obviously wasn’t an Ashton Valve! In May of 1894 many people living in the town of West Bay City were terrified by the explosion of a boiler in the local planning mill. Buildings in the area were badly shaken up and the sidewalks of buildings nearby were littered with the glass from broken windows. The mill itself was wrecked and the boiler blown into 4 pieces. The engineer was blown against a sewing machine, cutting his lungs and heart out. Brick was thrown for a quarter of a mile. The late engineer was known to have a habit of running boilers with low water, claiming it was more efficient. In the years between 1885 and 1895, there were an average of 200 boiler explosions a year. Between 1895 and 1905, there were 3216 boiler explosions in the United States, and average of one a day, resulting in 7600 deaths and countless injuries. As recently as 2017, a man in Revere Mass died while tinkering with a faulty boiler. The explosion blew out the basement windows and a door clean off the hinges. There is an old quote “Necessity is the Mother of Invention”. The time was ripe for a major improvement. Time to introduce Henry Ashton. Henry was born in Norfolk, England in 1846. His basic schooling was supplemented by a course in mechanical and steam engineering. He arrived in Boston in 1869 with his wife Emma and a 2 year old son Alfred. He found work at the Hinckley Locomotive Works on Albany Street. He invented the lock up pop safety relief valve for steam engines in 1871 while working as the superintendent of refilling at the Eagle Sugar Refinery in Cambridge. He opened up shop at 138 Pearl Street with 3 other employees under the name Ashton’s Lock Safety Valve Co. He was burned out by the Great Boston Fire of 1872. 67 acres of what is now known as the business district was destroyed with the loss of 767 buildings. Wooden buildings, high winds, and a shortage of horses to pull firefighting equipment all contributed to the destruction. 1873 finds the company at 9 Rowes Wharf by the waterfront. In 1874 they moved to 261 Purchase St where they stayed for 4 years. The Cathedral File in 1878 burned the company out from their location at 93 Federal Street. Finally in 1879 they were able to attain some stability when the company moved to 271 Franklin St. They were at that location for 27 years. Another fire hit them in 1892, but the damage was minimal. The building was 4 floors to handle a business that had been growing rapidly since the introduction of the pop safety valve. In 1900, a fifth floor was added to keep up with the demand. They were always busy. In 1885, the Railway Purchasing Agent trade journal quoted the company as stating:” Ashton Valve has not discharged a man on account of any falling off in orders, nor run less than 10 hours a day during the last 4 years. The works are now running overtime in some departments”. 1892 was an important year for the company as they purchased the plant, patents, materials, and business of the Boston Steam Gage Company. As their trade journal release stated: “The reputation gained by nearly 20 years’ experience in the manufacture of safety valves and the widely recognized quality of the products of the Ashton Valve Company will be the only guarantee needed for the unsurpassed quality of the goods we shall put upon the market”. I find it surprising that it took them 21 years to get into the manufacture of gauges as they are the perfect complement to the other products they produced. And it wouldn’t be long before Ashton Gauges were as well known to the industry as the safety valves. History has shown that the gauges are what Ashton Valve is best known for today. at least on Ebay, where they can sell for substantial amounts of money. There was one listed a couple of months ago for $1700 dollars. They are works of art and quite popular with collectors and steam punk enthusiasts. 1895 was notable for the death of Henry Ashton, the company’s founder. Most of his responsibilities would be taken over by his son Albert, who had attended MIT, and would be an important figure in the daily operations of the company for the next 27 years. In the years between 1895 and 1922 the company produced 440,828 pressure gauges, the peak years being between 1915 and 1920. Trade shows, exhibitions, and conventions have always been an important part of any sales organization. They are essential opportunities to acquire new accounts, enjoy old customers, and check out the competition. These shows, as well as the many advertisements in trade journals, and the salesmen and distributors the company had all over the world kept the profile of the company high. The reputation of an Ashton valve or gauge as a long lasting top quality product was always heavily advertised. An ad in a 1921 trade journal read “Ashton products, unequaled for quality, efficiency, and durability, higher in first cost but cheapest in the end”. This was a time when you repaired things, you didn’t throw them away. The company had a full service gage repair service. A few of the shows the company attended are worth mentioning for the awards they returned home with. At a Boston show in 1874 the Mass Charitable Mechanics Association awarded them a silver medal for their pop safety valves. The Mass Charitable Mechanics Association was founded in 1795 with Paul Revere as its first president. It’s founding members first met to address the problem of runaway apprentices but soon evolved into a group committed to promoting the mechanical arts and raising money for member’s widows and families. It still exists today. Is anyone here involved with this group? Ashton Valves received a special premium award at the 1881 Cincinnati Industrial Exposition. In Chicago, they received another medal for pop safety valves at the 1893 World’s Fair. They crossed the Atlantic Ocean in 1900 for the Paris Exposition, bringing home 1 silver and 2 bronze medals. In 1904, at the St. Louis World’s Fair they received another silver medal for their display of safety valves and gauges. The late 1800’s were times of active growth in labor unions nationwide. Both the American Federation of Labor and the Boston Central Labor Union were gaining strength. After a walkout in 1895, Ashton Valve restored wages that had been reduced the previous year. In May of 1901, 53 machinists walked out of the Ashton Valve Company as part of a nationwide strike for shorter hours with no reduction in pay. In June the local strikers committee accepted the Ashton Valve proposal of a 9 hours day with no cut in wages. The workers of the time were working 6 ten hour days per week. In 1912 the Boston Molder’s Union #468 went on strike which resulted in a minimum wage of $3.50 per day! The Franklin St building they had occupied for 27 years couldn’t handle the business anymore and in 1907 they purchased land in Cambridge and built a 4 story 45,820 square foot building. Located at 161 First St, the building still stands today with the Ashton Valve name clearly visible on the granite lintel above the front entrance The Cambridge Historical Commission has some wonderful old newspaper articles on the building. It was built at a cost of $67,000. It was one of the first modern factories built in what now is the Kendall Square area of Cambridge. Built on reclaimed swamp land, the facility featured modern bathrooms and electricity throughout the entire building. The 4 floors included a fireproof store room for paper drawings, iron shop, foundry, and a special testing room in the back with it’s own boiler capable of creating steam up to 400 psi. It was obviously designed with the idea that a better environment would provide a more productive work force. In 1919, Albert Ashton introduced a course in modern production methods. The object of the course was to train the men in the principles of foreman-ship, to develop their qualities of leadership, and to give them a broader view of industry as a whole. Mr. Ashton, the president of the company, who is the originator and organizer of this movement, thought that course would help develop the men who took it as well as benefit the plant through increased efficiency created by better cooperation. He was also of the opinion employee relations would be strengthened because of the more careful handling of problems by the trained foreman. This was quite a contract to the Captain Bligh mentality used by many foreman and supervisors back then and even today. The business was still growing. The 1920’s and 1930’s were the peak years of the company’s influence. Their profit for the year 1916 was $182,234 or a little over 4 million in 2018 dollars. The year 1919 showed a profit of $214,178 or around 3.6 million in today’s dollars. Both numbers are pre-tax dollars. By 1922 there were around 250 employees. Ashton Valve had satellite offices in New York City, Chicago, London, San Francisco, Mexico City, Philadelphia, St. Louis, Cleveland, Genoa, Vienna, and Paris. The company helped form the Kendall Square Manufacturers Association and the Cambridge Industrial Association, which later became the Cambridge Chamber of Commerce. They were instrumental in starting a baseball and bowling league with other companies in the East Cambridge area. 1922 also saw the death of Albert Ashton, Henry’s son. He had been managing the company since Henry’s death in 1895. His brother Harry, who was the sales manager at the time, took over some of his administrative responsibilities. Business slowed in the 1940’s. Diesel locomotives, gas fuelled automobiles, and electricity as the main source of power all contributed to the decline in sales. According to the 1957 book “Atomic Power – It’s Significance to the Management of a Relief Valve”, “The Ashton Valve was a prime factor in the steam locomotive or railroad business, enjoying it’s best years in the late 1920’s and early 1930’s. It’s contribution to the overall sales is one of diminishing proportions, another example to be anticipated when a company does not assume a responsible role in the design development and manufacture of competitive products for an ever-changing market.” Unfortunately for Ashton Valve, the company never ventured far from the production of their steam related products.

Ashton Valve merged with the Crosby Steam and Gage Company in 1948, sold the building to Nicholson & Co., an industrial adhesive manufacturer, and moved with Crosby into the old Winter Brothers Tap and Die building in Wrentham, MA. The Wrentham building was torn down in 2012, Crosby was purchased by Tyco and still operates out of a facility in Mansfield, MA. https://www.smokstak.com/forum/attachment.php?attachmentid=338041&d=1561734973 Rick Ashton

2 Comments

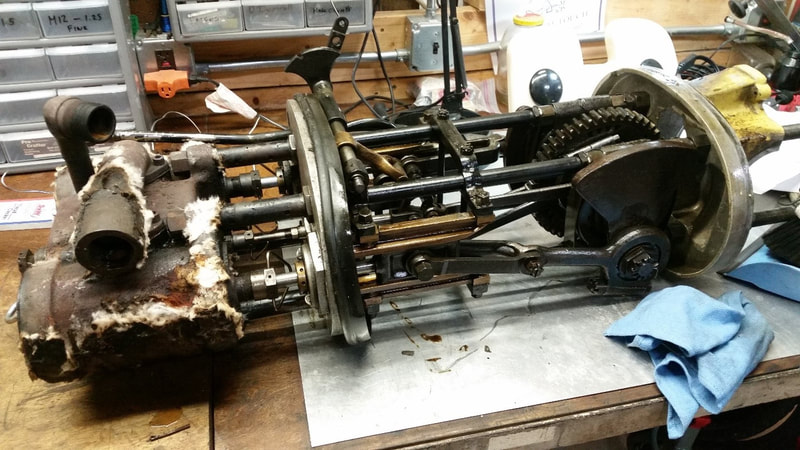

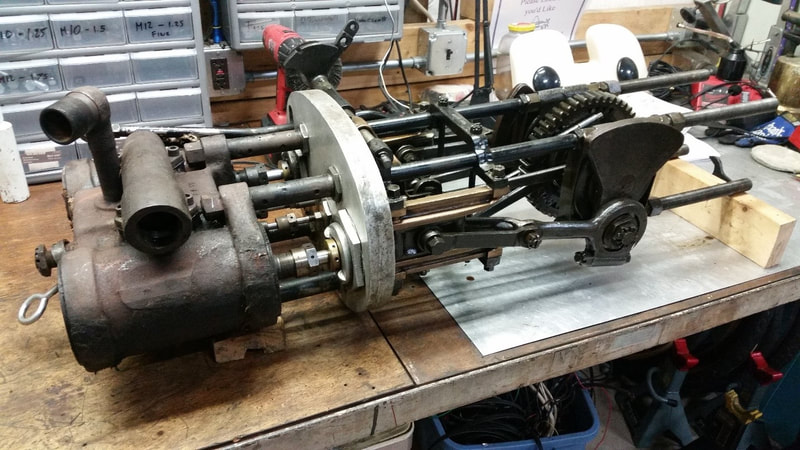

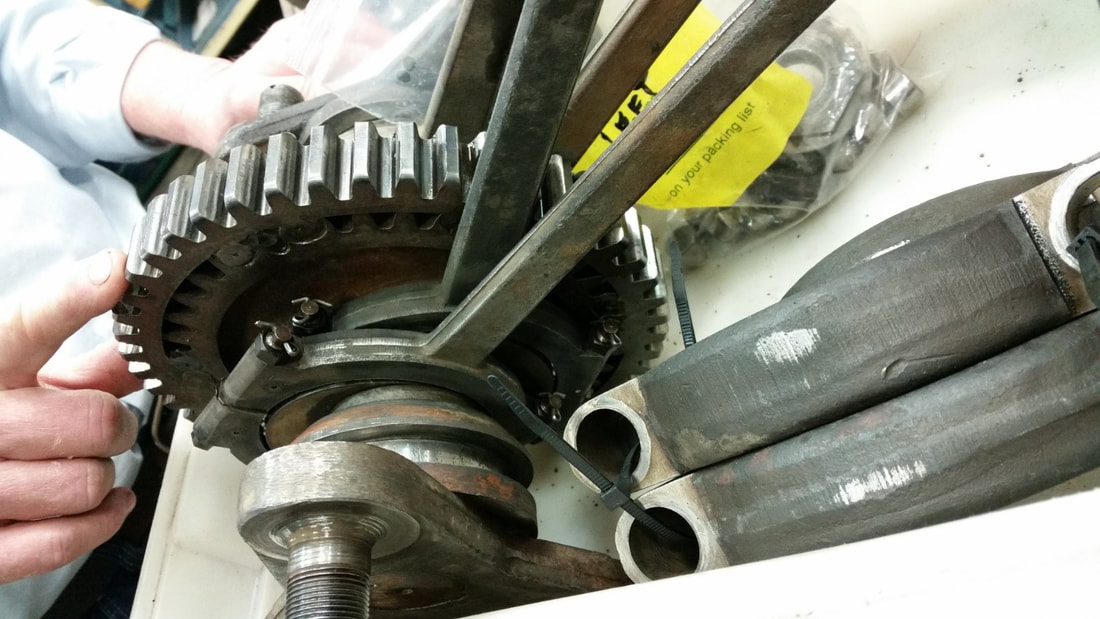

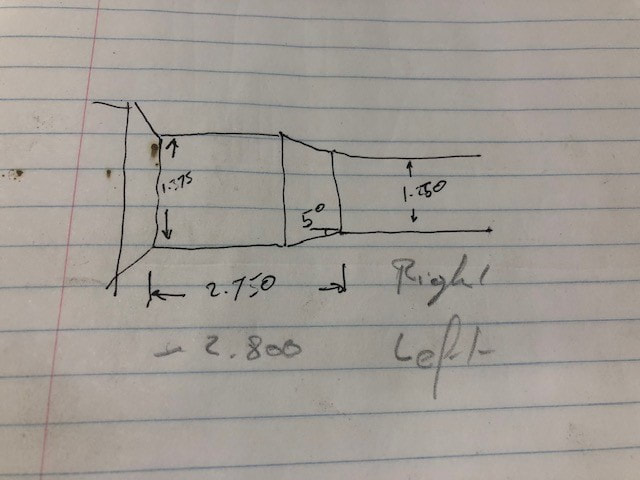

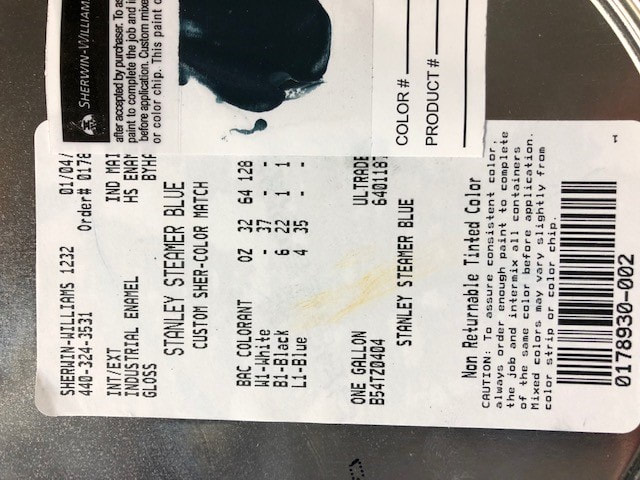

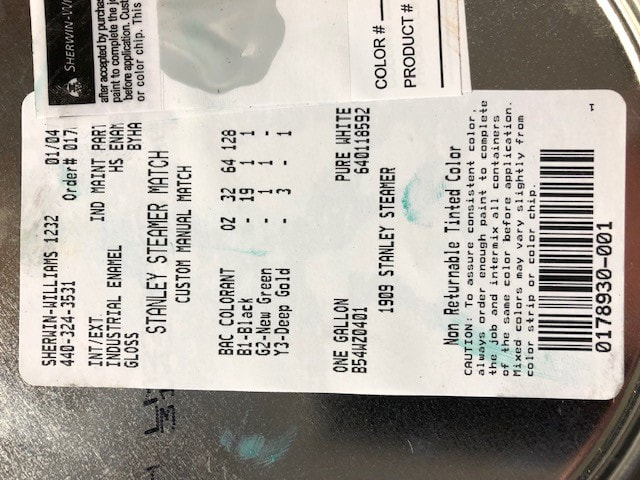

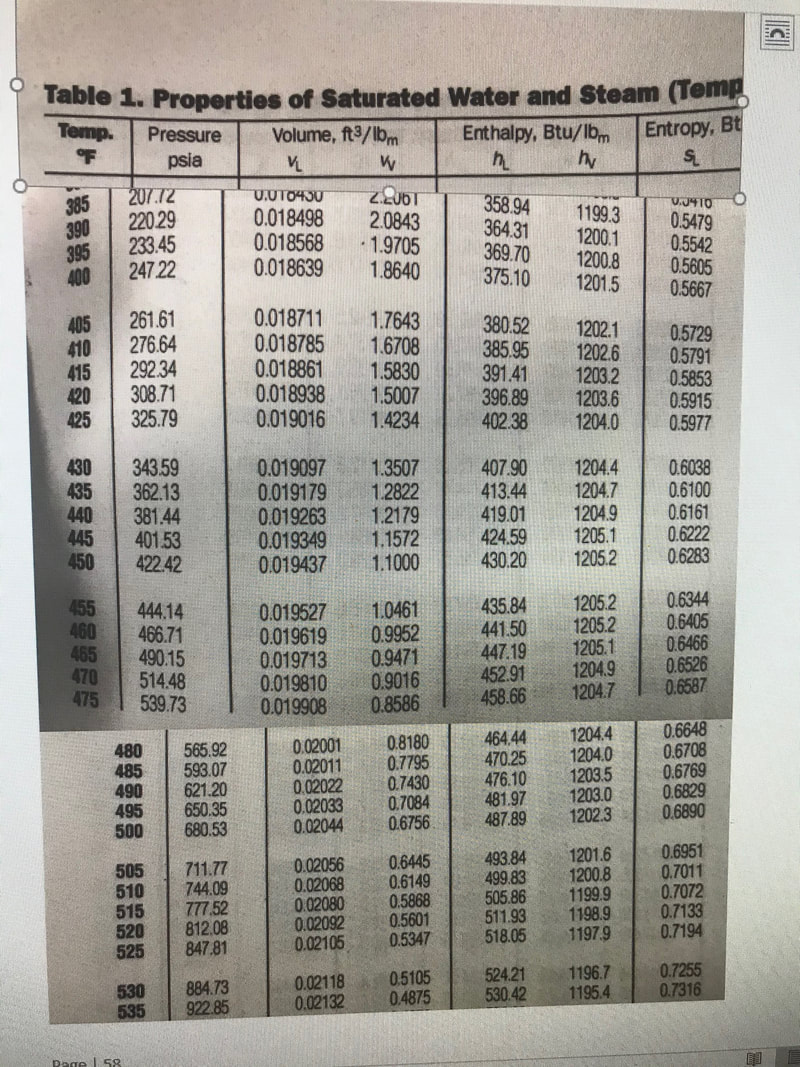

Engine Block Unscrew elbows from the engine block and remove copper covering. It will expose oil soaked insulation which needs scraping off. I made a lifting hook mounted on the back to assist in moving the engine. Valve Cover The valve cover has a hole in it for the drip valve. The pipe used to help take the unit out of the car can be used as a fulcrum to wrench the cover off. It should be so oil soaked that it should screw off easily after you get it loose. One of the ears is missing which led me to modify a pipe to use against the remaining ear. It worked fine. When reassembling, the cover has packing in the top and needs removed and replaced with a strip of 1/8” packing. The cover was replaced with a new one Don Hoke had in stock in 2019. The valve surface should be smooth and not curved. Steam pushes the valve against the block and creates a seal. Gearbox The oil level in the gearbox should be about 1 1/2 “ from the bottom while in the car. Bearings and sliding/turning surfaces should have minimal of .001-.003" clearance. It is easy to over-tighten bolts, and looser is preferred over too tight, especially with cam and crank rods. Make copper shims to space everything appropriately. Crank gear The crank gear is significant as it has a larger gear welded on top of a smaller gear. This was a fairly common practice as road conditions improved over the years allowing higher speeds and welding an existing gear over the original one was a low cost option to replacing the entire crankshaft. Rear Axle Differential Removing the rear wheel requires a special puller that fits in the hub. The complete axle with wheels weighs 394lbs. The main item to keep in mind is that play between the planetary gear and the spider needs to be as close to 0.001" as possible with less being more desirable than more. In the case of this car, there was so much play that the gears barely connected, resulting in catastrophic failure of all three spider gears as well as damage to the case. Adjustments to this play is achieved primarily through shims between the planetary gear and the inner bearing but also through shimming the cross members so that the case still fits over the assembly. The picture on the left shows a bit of the shims. on the right side, the housing is assembled over the differential, still allowing the axle to pivot. Axles Moving the planetary gears in ended up causing the axle to shift inwards on the rear end and the clearance between the wheel and rear-end disappeared causing the wheel to lock up on the driver's side and rub on the passenger side. In 2018, I disassembled the rear end again. Jim Wright built up the steel and I machined the end up a quarter inch further out. The Wheel is a press-fit with the nut torqued to around 200 ft/lbs on the 5deg cone splitting the 1 1/4" and 1 3/8" section. The end result is that the wheel fits better but there is no longer space for a washer under the nut on the end of the axle ,and in the case of one of the axles, a 1/16" cotter-pin hole needed to be drilled at the end of the shaft. The end result pushed the wheel out about 1/4" inch. The collar was turned and polished to accept the new oil seal from McMaster: 5154T29 (SKF 17231) for shaft 1.750" and bore 2.250". The collar is put on the axle with some gasket material. One axle has a middle diameter of 1.325" whereas the other is wider at 1.360". I did not change it. The outer bearing is a sealed unit and should not need any care. Before and After (2018) The shortest the secondary piston and metering rod can be is to a point where it gets right past the opening. This will also provide the most oil to the cylinder. The absolute longest would be a point where it almost reaches the intake port. Very little oil will be pumped with this setting. The rod is adjusted by moving the nuts in or out and then tightening them against each other. To set the limit of the primary piston, place the metering rod towards the end of the hole, push in the primary piston until the two meet and mark the spot with a marker.  Once back in the car, screw the piston into the mount until the most forward motion reaches the mark. Brass Cleaning As There is a lot of Brass/ Copper on this car, polishing it will take a fair bit of time. Polishing very tarnished Brass/Copper is best done with a soft cloth polishing machine and red rouge for a rough clean. White rouge on a finishing cloth seems to leave a build-up and the finish does not improve. The likeliness for a Polishing machines to grab and throw parts to the ground at great velocity is directly proportional to their fragility and replacement cost. Polish The best way I have found to clean by hand is through the Wizards product line. A buddy introduced me to Wizards Metal Polish, which is an impregnated piece of cotton. It worked well but not nearly as well as when I added Wizards Metal Renew to it. Other products tried were : Mothers Billet Cleaner (Good) Brasso (Poor) Most products sold at flea markets and products like Oxy-clean have found their way into the trash bin. Saving the shine As of 2019, I have not found a suitable product that works. I stayed with Wizards Metal sealant as it came in a package with the other Wizards Products. It seems to help a little. Eastwood has a product in a spray can that almost looks like a clear coat. Neither really kept the Brass from turning yellow and the Eastwood product required the buffing wheel to remove it. Paint By the end of 2018 the paint started coming off sections of the car in sheets. On other parts like the hood and the front, there was a lot of burn damage. For a short time, I considered stripping the car down completely and have it repainted professionally, but veered away from that as the vehicle is getting a lot of use and the time it would take to do so would probably turn into a full restoration: as well as the slim chance of a fine pint job remaining that way for any length of time lead me to search for an alternative Gloss paint that would be durable. I eventually settled on Sherwin Williams Industrial Enamel. My Neighbour Arthur helped with prep and paint of the large flat section, as I did not want brush marks. The hood is a combination of prep styles as well as some brushing and some spraying. The paint on the side was in very poor shape, and was not sticking to the wood at all. The passenger side seemed to be less affected by it. Early attempts included trials with and without primer as well as brushing VS spraying. Arthur was of great help here. Eventually, we settled on a sand-able primer and spraying the enamel after making sure the primer was smooth. The gloss is not nearly what I would expect from automotive paint but I will try wet sanding it next winter. It takes a long time to dry. The dark blue stripe with the 1/8" light blue stripe within was achieved by putting a 1/8" piece of masking tape and paint the dark blue over it. I found that this paint came out very well if the masking tape was removed immediately after painting, as it allowed the paint to flow. Multiple coats of enamel tend to cause it to crinkle, probably since it takes so long for this paint to dry. Resources Steam Oil: Siphon-a-min 1000 Brennan oil 970-247-3054 Machining of complex parts: Rempco 231-775-0108 Boiler repair: Don Bourdon (802) 457-3787 Tank Sealer: CHEMSEAL B2 TANK SEALANT CS3204

Brass: Wizards 3004.2982 11011 Metal Polish. Wizards Metal Renew_Silver Polish, Aluminum Car Care, Motorcycle Copper Cleaner. Wizards 11021 Power Seal Metal Sealant. |

Archives

December 2022

Categories

All

|

|

|

Steam Car Network functions as a resource for all steam car and steam bike enthusiasts. The website is constantly updated with articles, events, and informative posts to keep the community alive and growing. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or concerns at the email address below and we will promptly reply.

[email protected] |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed